The Case Study series is my mini-exploration of unique, complex and fun game mechanics and systems from other games that I enjoy, to act as inspiration and ideas for my own games. The series focuses particularly on clever (and not-so-clever) uses of procedural generation, since that’s what my games will focus on. I think an important part of being a good game designer is looking at what other games in my genre do right, so that’s what I’m going to do!

And in this episode, I’m looking at the big one. The Great Big One. The most popular and well-scrutinized example of procedural generation, and its pitfalls, in the history of video games.

That’s right. Today, we’re talking about procedural generation in No Man’s Sky. And that should come with a big disclaimer right off the bat.

I enjoy this game. It isn’t a game I would call a favorite of mine, but I still really like it and I appreciate the developers and the work they put into it. However, it does have flaws, and today I am going to discuss those flaws. But I wanted to make clear that I do really love this game and I’m not trying to say it’s bad by discussing its weaker points. So please bear that in mind while you read.

And now, with that out of the way, let’s talk about the parts of this game that suck.

How can something so big feel so small?

No Man’s Sky has one of the most mathematically impressive uses of procedural generation in gaming, which is to say that it has some really show-stopping numbers. It boasts literally eighteen quintillion planets (did I stutter?) and a wide variety of procedural flora, fauna and environments. If you hadn’t played the game, you would think that this must be the biggest achievement ever – a literally infinite universe, with endless possibilities.

But then you actually play the game.

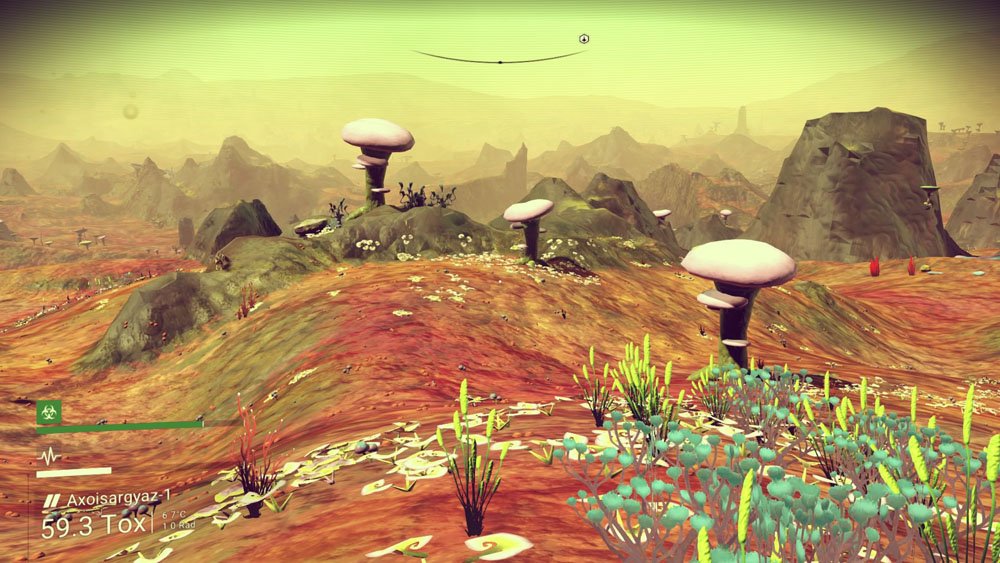

The first ten minutes are magical. I know mine were. Stepping out into my very first alien planet, and seeing all of the incredible plants and animals with all of their strange and alien shapes and colors, was truly astonishing. I remember putting down the controller and sitting back in my chair, just to have a moment to take it all in.

But gradually, as the game wore on and I visited a few more planets, I began to realize how truly limited the procedural generation really was. All of the plants and animals, while visually distinct, looked and acted just about the same. The animals in particular only seemed to have two AI scripts – either they ran away or tried to fight me, with nothing complex or interesting in between. They didn’t interact with each other organically, didn’t feed on the plants or attack each other or anything. The space stations and structures all looked and behaved the same, and were scattered about seemingly at random, rather than integrating naturally into their surrounding environments. And even the plants started to look the same after a while, once I had seen just about every remixed asset that went into them. It just felt so… empty.

Even the NPCs were generic and boring. They looked really cool and had funky names, but eventually I realized there were only a few hand-designed alien races with predetermined appearances, rather than a wide array of weird and wonderful procedural creatures. There was also a limited pool of names and titles to choose from, as Angry Joe hilariously demonstrated by continually running into Liquidator Amru. I couldn’t interact with them naturally in conversation, only solve their weird little dialogue puzzles.

So how does the procedural generation system even work? And why, despite being technically impressive with a lot of complex mathematics behind it, is the final product so shallow, plain and underwhelming?

There are a few reasons, I think, and all of them are good learning opportunities for how to implement a good procedural generation system into your own game. So let’s take a look at each one.

Not enough assets to choose from

The way the procedural generation system works is essentially the same as in our previous article on the Nemesis System in Shadow of War. In brief, the game has a bunch of premade assets for animals, plants and environments that it mixes together at random, using a random 64-bit seed – hence the quintillions of possible combinations.

But unlike the huge variety of assets in Shadow of War, this procedural generation system has slim pickings – only a handful of assets to choose from. This is probably due to the art team being so small, given that Hello Games, the maker of the game, is a very small studio indeed. To paraphrase the Internet Historian: “I’ve never seen a smaller team behind a Triple-A game.”

And I think that’s a big part of why the game feels so limited. It’s why you start to see the patterns in the generation system very quickly and become bored of them. There’s just not very much variety to choose from, and all of it is surface-level – none of the customized depth of the Nemesis System, which tailors its procedural generation to the player’s choices in a way that makes it feel much more organic and alive. In comparison, the procedural generation in No Man’s Sky is about as deep as a paddling pool.

It’s essentially like if you were tasked with procedurally generating a bunch of birds, but you only had two base bird models to mix together, bluejays and sparrows. You’d end up with a whole lot of technically different creatures, sure – maybe a bluejay with a sparrow’s tail, or a sparrow with a bluejay’s head – and you can claim all you want that there are “millions of possible combinations.” But in the end, they’re all really just a bunch of sparrows and bluejays.

But let’s get back to that second problem: the lack of depth.

Wide as an ocean, deep as a puddle

It’s been said a lot already, but I’m going to reuse this analogy: No Man’s Sky is a game with fantastic scope and basically zero depth.

For one thing, its systems don’t interact with each other. The animal system doesn’t interact with the plant system, the language system doesn’t interact with the ruins system, and so on. They’re all in their own little code silo, which prevents organic, systemic interactions from arising. In games like Far Cry, for example, the tiger AI system knows how to interact with the people AI system (flesh-mauling), and in Breath of the Wild, the fire AI system can interact with the wood and grass AI systems (by setting them on fire).

Imagine how much deeper and cooler the game would feel if, for example, each procedurally generated animal was placed on a food chain and was preyed upon by larger animals, and you could spot animals fighting each other, snacking on their preferred flora diet, maybe even nesting or having babies. Imagine if the aliens actually had dialogue trees and unique AI, and could give you information about the local wildlife, maybe giving you clues about how to deal with that rampaging raknar beast over there, and… etc. etc. In the end, you could think of a thousand ways for the procedural generation system in the game to feel more alive and dynamic, but what matters is that no matter what you think of, the game doesn’t do it. Hence why this world, so seemingly infinite, feels in practice like a static, dead wasteland where nothing truly interesting ever happens.

Yet there’s a bigger problem, and this one, I think, is what really kills the game for me and a lot of other players.

Where’s the fun?

The lesson that has been drilled into me by all of my computer science and game design professors, from the start of my schooling to the end, is that your game can have all the cool graphics and fun music you want, but at the end of the day, it won’t mean a thing if it isn’t fun. If the game doesn’t have a compelling gameplay loop, or a good mechanical hook, or a strong plot and characters, it just won’t be any fun for the player, regardless of the pretty package you put it in.

Similarly, visually plain games can be incredibly compelling if they focus on getting the gameplay, plot and characters right, or if they have so much substance and impact that it makes up for the somewhat plain packaging. Just look at games like Undertale and Thomas Was Alone. They have minimalistic graphics and don’t look like much at first, but they make up for it with the things they do amazingly well – in the case of Undertale, by being an incredibly strongly plotted and subversive game with well-designed characters.

In other words, all the advanced mathematics behind a system, all the huffing and puffing about millions of possible experiences, all the technical prowess in the world, doesn’t mean a thing if the player doesn’t enjoy it.

The procedural generation in No Man’s Sky doesn’t make the game more fun. It doesn’t fundamentally improve or deepen the experience, and while it makes sense in a game about exploration and discovery, it isn’t deep, complex or interesting enough to carry the entire game by itself, and it shows. It really shows.

If the game had a solid gameplay loop, or a good plot, it could have been a fun addition to a good game. But because the game lacks a solid gameplay loop and has nothing in the way of a compelling plot, the player’s focus goes to the procedural generation when looking for the fun, and because of this, the procedural generation looks all the more lacking. It just makes the game that much more disappointing.

I’ve seen some critics say even worse than that – that it’s just there as pretty window dressing on an otherwise boring and pointless survival game, something that the developers could brag about in the tabloids – and I don’t agree with that harshness. I don’t think the game developers are swindlers who set out to deceive people with their grand claims of the biggest, coolest procedural generation system ever made. If anything, I agree with the Internet Historian’s compassionate, well-designed analysis of Hello Games as well-meaning, but badly equipped developers who didn’t really know what they were promising and weren’t ready to make a Triple-A game on the scale that they did, and were unfairly attacked and scorned as a result. Anyone who was part of that initial release controversy should watch that video, because it paints a very affecting picture of Hello Games and Sean Murray that might surprise you – and hopefully give you a little empathy for them.

But I can’t deny that there’s honestly no point to there being procedural generation in this game, because it adds literally nothing to the experience and isn’t fun. And there’s absolutely no point to a game if the player isn’t having fun playing it. (Except for subversive games like Spec Ops: The Line, maybe. But those are the exceptions.)

There’s no point in having an incredibly advanced procedural generation system if it doesn’t mean something to the player, or add to their enjoyment. And that, for me, is what really sounds the death knell for No Man’s Sky.

A good game with flaws

I’d like to say again that this is, fundamentally, still a pretty good game. It’s not the game that was promised, but with recent updates it has become a lot more compelling and fun, and a lot of the issues discussed in this article have been improved upon over time, such as adding more diversity to the fauna and flora. I felt the need to dissect its issues today because I think there is a lot we can learn from them, but at the end of the day, I still recommend this game to my friends all the time, and I would recommend it to you, the reader, if you’re also interested in exploring how procedural generation can work (and also not work) on this massive of a scale. So definitely still check it out!

What can we learn from this?

The lessons I took away from No Man’s Sky are as follows:

- Your procedural generation system should be fun for the player, and add to the experience of the game. It shouldn’t just be something you can brag about having.

- The system needs to have enough fundamentally different assets to make the procedural generation varied and fun, even if the player has been playing with it for a while. It needs to still be able to surprise you. Don’t think about combinations – think about variety.

- Procedural generation systems should have depth, rather than just being surface-level. They should interact with other systems and create organic interactions, and have rules that are fun for the player to learn and take advantage of.

And most importantly, it doesn’t matter how wide the ocean is or how much math went into making it. It’s all about the depth.

Next time, we’ll discuss a particular roguelike I really enjoy. It’s a dark sort of dungeon. You might be familiar…

Sources and further reading

https://kotaku.com/a-look-at-how-no-mans-skys-procedural-generation-works-1787928446